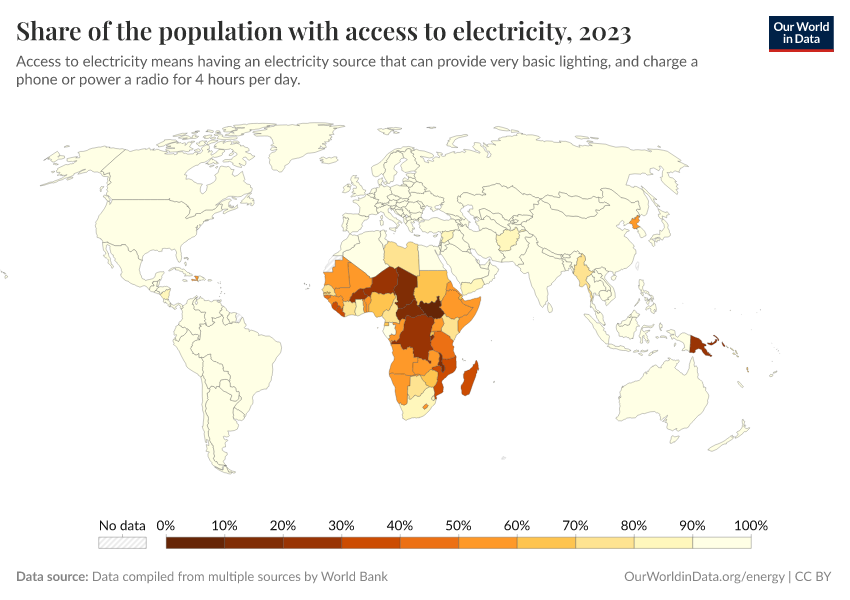

Electricity access in Bangladesh has transformed over my lifetime: from around 15% of the population 30 years ago, to 99% today.

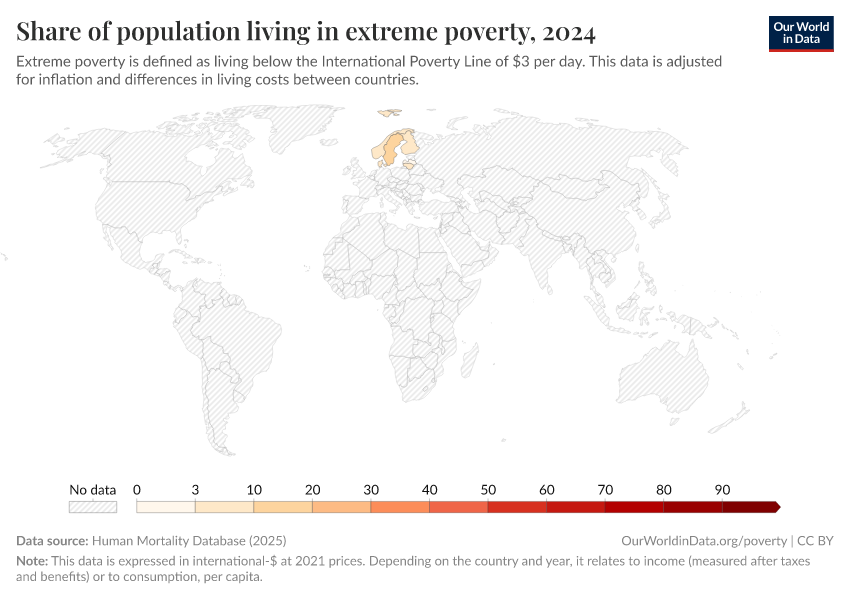

But progress on clean cooking fuels has lagged far behind. Fewer than 30% of households cook with gas, electricity, or improved stoves; most still rely on wood, crop waste, or straw. The chart shows that clean fuel usage is well below the levels reached by its Asian neighbors.

The costs are huge. Using biomass for cooking damages forests and harms health because people breathe in smoke and particulates. In Bangladesh, deaths from indoor air pollution are higher than the average in low-income countries, even though those countries usually have worse overall health. Indoor air pollution is close to being the country’s largest risk factor for early death.

Why has progress been so slow? The main barrier is economic. Bangladesh produces very little liquefied petroleum gas (LPG), relying instead on volatile imports. Its lack of domestic distribution networks also pushes prices, making clean cooking fuels expensive for consumers. Some of Bangladesh’s neighbors — like India — have given subsidies to help households switch; Bangladesh has not, making clean cooking fuels less affordable.

Cultural factors also matter. Biomass is often seen as “free” and convenient, and families are used to traditional cookstoves and the flavors they generate. They might be unaware of how damaging this pollution is to their health and skeptical of the damage that alternatives such as LPG could do.

Read my colleague Max Roser’s article — “The world’s energy problem” — for a global perspective on this issue →